The Vuelta a Espana began on this day in 1942. Its 19 stages covered 3,683km and the winner of both the General Classification and the King of the Mountains was Julián Berrendero. He also won the previous year, when the race returned after the Spanish Civil War; after this edition the race wasn't held again until 1945 due to Spain's economic problems and the Second World War.

|

| Crupelandt signs in at a race checkpoint |

The

Tour de France has started on this day more than on any other:

1912, 1929, 1931, 1937, 1948, 1949, 1973, 1977 and

1990 - and it starts again today in

2012. In 1912, the fifteen stages covered a total of 5,289km. One rider, a man named Stéphanois Panel but commonly known by the name Joannie, came with a bike fitted with a derailleur gear system - this was the first time such a device had been seen at the Tour. He called the system Chemineau and had invented it, and the handlebar-mounted fully-indexed lever that controlled it, himself. It seems to have worked well, but race organisers felt it made the climbs too easy and when he abandoned they persuaded the other riders that it was unreliable, then banned derailleurs for the next quarter of a century. The race started from the enormously popular Lunar Park on the Avenue de la Grande Armée, a far more prestigious location than any Grand Départ so far and evidence that the Tour was becoming something far greater to the French than just a bicycle race.

Gustave Garrigou, the previous year's winner, was the favourite. His Alcyon team had signed up Odile Defraye to support him, but Garrigou sensed that he might prove to be a rival and persuaded the other team members to object to his inclusion for the Tour. Alcyon refused to back down and Defraye remained in the selection. Charles Crupelandt (who became a hero during the First World War, but was then accused of a crime he probably didn't commit and was banned from racing for life - probably because his rivals pressed the National Federation to do so; by the time he died in 1955 he'd had both legs amputated and had lost his sight) won an uneventful first stage in which Defraye was 14th at +30'54 and Garrigou 21st at +41'53".

|

| On the Aubisque, 1912 |

During Stage 2, Garrigou and Defraye got away together. Defraye won, Garrigou recorded the same time - however, due to the points system then used to determine the General Classification leader, Defraye moved into second place overall behind Vicenzo Borgarello who had picked up enough points along the way to become the first Italian rider to ever lead the Tour de France. In Stage 3, they both got into a fourteen-strong break before Defraye attacked at the foot of the Ballon d'Alsace (the Tour's first mountain in 1905) and was first to the top; then the fantastically fast (if frequently unfortunate) descender Eugène Christophe dropped him on the way down and took the stage. Defraye was now leading overall

Defraye appears at this point to have had no intention of standing in Garrigou's way - either that or he was a gentleman, because when Garrigou punctured on tacks thrown into the road (probably by French fans trying to hold up Belgian riders) he stopped and waited. Garrigou, however, had been impressed by Defraye's performance so far and was now touched that he'd waited. He too was a gentleman, and he told him to go on without him rather than ruin his own chances. This meant that, for the first time, a Belgian rider stood a very good chance of winning overall - most of the other Belgians then completely forgot about their teams and rode for him. Race director Henri Desgrange, who was fiercely opposed to riders helping one another, was of course incensed.

Christophe won Stage 4. A useless sprinter, Christophe climbed well and descended even better; therefore his best way to win a stage race decided on points was to escape the peloton and hope for the best with heroically long solo breaks - this is what he did on Stage 5, winning after the longest solo break in Tour history (315km) and earning enough points to share the leadership afterwards. On Stage 6, Defraye had recovered from his knee problems in Stage 5 and attacked in the mountains. Octave Lapize was the only man able to go with him and managed to win the stage when Defraye punctured, which enabled him to replace Christophe in sharing the lead. Defraye then attacked again on the Portet d'Aspet in Stage 7 - Lapize tried, but this time he couldn't respond. Borgarello won Stage 8, but was now too far behind for it to make much difference.

During Stage 9 Lapize abandoned in protest at the Belgian riders working for Defraye and his La Française team mates Crupelandt and Marcel Godivier left the race that evening for the same reason; Christophe thus moved into second place in the General Classification. There were six stages to go and he was 20 points behind - with all the Belgians now working for his rival, Christophe could only possibly win if Defraye left the race. He didn't, and kept doing well, eventually becoming the first Belgian to win the Tour with an advantage of 59 points. However, had the winner have been selected according to accumulated time, the General Classification would have looked very different. Desgrange recognised this, and the following year the race was decided that way.

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Odile Defraye (BEL) Alcyon 49p

2 Eugène Christophe (FRA) Armor 108p

3 Gustave Garrigou (FRA) Alcyon 140p

4 Marcel Buysse (BEL) Peugeot 147p

5 Jean Alavoine (FRA) Armor 148p

6 Philippe Thys (BEL) Peugeot 148p

7 Hector Tiberghien (BEL) Griffon 149p

8 Henri Devroye (BEL) Le Globe 163p

9 Félicien Salmon (BEL) Peugeot 166p

10 Alfons Spiessens (BEL) J.B. Louvet 167p

(Note that in the event of two riders tying on points, accumulated time would be taken into account - hence Alavoine and Thys do not share 5th place)

In 1928, organisers had worried that the plain stages were not as interesting to fans as mountain stages (which is true, in the case of many fans) so they experiemented with running them as long individual time trials instead. Unfortunately, even the most boring of flat stages appeal to everyone who appreciates cycling on some level, if only for the sheer spectacle of the peloton going by, while time trials appeal only to those with an interest in the more technical aspects of cycling competition; as a result, a dangerously high percentage of the population simply lost interest. In

1929, they did away with the individual time trials altogether, but the race had returned to something more like standard format - there were 22 stages of which three were team time trials, covering a total of 5,286km, though they reserved the right to reintroduce individual time trials should any stage be ridden at an average speed less than 30kph (in 1930, organisers decided to do away with time trials altogether; they didn't reappear until 1934).

Another outcome of the 1928 race was a desire to prevent any one team dominating the race, as had Alcyon when they took all three steps on the final podium. Organisers had not yet decided that national teams were the way forward (that came in 1937 and lasted into the 1960s) but officially, trade teams were not in the race and, as a result, riders were simply the 1st Class, which meant they were professional, or 2nd Class, which meant they were semi-professional (perhaps having a bike supplied free by a shop, but otherwise responsible for their own costs, or independent (which really meant "rich enough to pay their own way or happy to beg for scraps and sleep in hedges along the parcours"). Organisers had let it be known that anything looking suspiciously like collusion between riders who spent the rest of the year racing for any one particular team would result in prohibitive action, though they didn't specify what that action might be - last time they'd tried something along the same lines, in 1924 when they allowed the 2nd Class to set off with a two-hour head start one day and then when that didn't get the results they wanted tried to reverse the situation the next day, the riders had soon had quite enough of being messed around and threatened a strike, forcing Desgrange to back down. Their reluctance to give further details, therefore, tends to suggest that until somebody came up with the national teams idea they were completely at a loss as to what they could do about it. In view of that, one last petty rule change seems simply spiteful - in 1928 riders had been allowed to accept help when repairing punctures; in 1929 they had to do it themselves. It was also the first time that the race was covered by radio broadcasts.

Aimé Dossche won the first stage and held the yellow jersey until Stage 4 while André Leducq, Omer Taverne and Louis de Lannoy won Stages 2, 3 and 4. Maurice Dewaele became leader after Stage 4 and stayed in yellow until the end of Stage 7. Gustaaf van Slembrouck and Paul Le Drogo won Stages 5 and 6, then Nicolas Frantz won Stage 7. Dewaele punctured on that stage and lost significant time; Frantz, Leducq and Victor Fontan all shared the best overall accumulated time and so Stage 8 began with the unusual sight of three men each wearing a maillot jaune.

Lucien Buysse, who had won the Tour in 1926 but was now racing as a touriste-routier, attacked early in Stage 9 and was the first man to the top of the Aubisque, but Dewaele and Fontan caught him on the way down. Dewaele punctured again and lost more time; Fontan lost the stage to a Spanish rider named Salvador Cardona but slipped into the lead overall - and thus, at the age of 37 years and 21 days, became the second oldest man in Tour history to wear the maillot jaune (after Eugène Christophe, who was 37 years and 165 days the last time he wore it in 1922). However, just 7km into Stage 10, Fontan crashed: some eyewitnesses said he rode into a dog, other that he rode into a gutter, which raises the likely scenario that he rode into a gutter while trying to avoid a dog. His fork snapped, leaving him subject to the old rule that a replacement bike was only permitted if a race official had deemed the machine irreparable. Unfortunately, at this early stage, all the officials were stationed much further ahead and the director's car had already gone past. If he was going to remain in the race, his only option was to find another bike and take the old one with him to prove it couldn't be fixed so, after knocking on almost every door in the nearest village until he eventually found someone with a bike they'd lend him, he strapped his broken machine to his back and set off. He rode alone like that for 145km before the weight and the pain of the broken bike digging into his spine and ribs became too much, then he sat down by a fountain at Saint-Gaudens, overlooking the Garonne valley, and burst into tears. 171km away, Jef Demuysere won the stage and Dewaele became overall leader.

|

| Victor Fontan |

Some time later, Fontan was found at the fountain by the journalists Alex Virot (who would be killed in a motorcycle accident at the Tour in 1957) and Jean Antoine, who were producing reports for Radio Cité. They recorded his sobbing and, less than two hours later, it was broadcast. All of France felt for him and angry that, when he'd been doing so well, he could be robbed of victory through no fault of his own: Les Echos des Sports journalist Louis Delblat summed up popular feeling best with the following words:

"How can a man lose the Tour de France because of an accident to his bike? I can't understand it. The rule should be changed so that a rider with no chance of winning can give his bike to his leader, or there should be a a car with several spare bicycles. You lose the Tour de France when you find someone better than you are. You don't lose it through a stupid accident to your machine."

The next year, Desgrange had changed the rules. More than a quarter of a century after the first Tour, riders no longer had to seek official permission to replace a broken bike.

Leducq, Marcel Bidot, Benoît Fauré, Gaston Rebry and Julien Vervaecke won the next five stages. Dewaele was still leading overall and ended Stage 14 with an advantage of 18'20". Then, with just an hour to go until the start of Stage 15, he fainted. Alcyon requested that the start be delayed for one hour, which was granted, but he was obviously not a well man as the team propped him up on the start line before quite literally holding him upright all the way to the end of the stage (organisers did nothing at the time, which strengthens the argument that they had no idea how to respond to Desgrange's hated teamwork) and somehow getting him there only 13'25" after Vervaecke and losing only 2'49" from his overall lead. The next day, he'd recovered and kept his lead at 15'31" while Charles Pélissier (younger brother of Henri and Francis, who had competed in the Tours around the First World War) won the stage.

|

| Giuseppe Pancera |

Leducq won Stages 17 and 18 and Dewaele upped his lead to 18'20" again, kept it the same as Bernard van Rysselberghe won Stage 19, then added 10' by winning Stage 20. Leducq and Nicolas Frantz took the final two, but it was too late now. Demuysere had stayed in second place overall ever since Stage 16, but judges found on favour of an accusation that he'd accepted a drink outside of a feeding zone, where doing so was forbidden (until surprisingly late, conventional wisdom stated that it was best to avoid drinking as far as possible during strenuous athletic activity; so riders were limited to four bidons - about two litres - per race. Nowadays, of course, domestiques can be seen flitting to and from the team cars to collect fresh bidons for their masters at almost any point along the parcours). As a result, he was penalised 25' and fell into third place behind Guiseppe Pancera, who trailed 44'23" behind Dewaele.

Desgrange, who had seen Dewaele at the start of Stage 15, was seething (reading the history of the Tour, it's very easy to imagine that Desgrange spent most of his life moving from one level of fury to another. His management style was heavy-handed and he had a tendency towards pomposity and arrogance, but he appreciated jokers and, after divorcing his first wife, spent the rest of his life with a bohemian artist named Jeanne Deley, who filled their Paris home with all manner of other artists, characters and general eccentrics. His lighter side also came out during an ongoing row with the Mercier bike company, which is recounted as an aside at the end of this article). "My race has been won by a corpse!" he proclaimed, and immediately set about finding ways to prevent such a thing every happening again. The next year, as described above, trade teams were banned from the Tour.

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Maurice Dewaele (BEL) Alcyon 186h 39' 15"

2 Giuseppe Pancera (ITA) La Rafale 44' 23"

3 Joseph Demuysere (BEL) Lucifer 57' 10"

4 Salvador Cardona (ESP) Fontan–Wolber 57' 46"

5 Nicolas Frantz (LUX) Alcyon 58' 00"

6 Louis Delannoy (BEL) La Française +1h 06' 09"

7 Antonin Magne (FRA) Alleluia–Wolber +1h 08' 00"

8 Julien Vervaecke (BEL) Alcyon +2h 01' 37"

9 Pierre Magne (FRA) Alleluia–Wolber +2h 03' 00"

10 Gaston Rebry (BEL) Alcyon +2h 17' 49"

1931

24 stages, 5,901km.

Max Bulla won Stage 2 and took the maillot jaune - the only time it was ever worn by an touriste-routier in the history of the Tour. He benefited from the fact that riders in his class were permitted to set off ten minutes before the 1st Class professional riders, as was the case in Stages 3, 4, 6, 7 and 12.

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Antonin Magne (FRA) France 177h 10' 03"

2 Jef Demuysere (BEL) Belgium +12' 56"

3 Antonio Pesenti (ITA) Italy +22' 51"

4 Gaston Rebry (BEL) Belgium +46' 40"

5 Maurice De Waele (BEL) Belgium +49' 46"

6 Julien Vervaecke (BEL) Belgium +1h 10' 11"

7 Louis Peglion (FRA) France +1h 18' 33"

8 Erich Metze (GER) Germany +1h 20' 59"

9 Albert Büchi (SUI) Australia/Switzerland +1h 29' 29"

10 André Leducq (FRA) France +1h 30' 08"

"As the bicycle banged and jolted over the uneven ground, one yearned for company, for another human whose conversation would share the anxious misery of those uncertain hours. Yes, there it was, a vague outline of a hunched figure swinging and swaying in an effort to find a smooth track.

French is the Esperanto of the cycling fraternity, so I ventured some words in that tongue. C'est dur ("it is hard"), but only a grunt came back. For a mile we plugged on in silence, then again in French I tried: "This Tour - it is very difficult - all are weary." Once more, only a snarling noise returned. "This boorish oaf," I thought, "I'll make the blighter answer."

"It is very dark, and you are too tired to talk," I inferred, sarcastically. The tone touched a verbal gusher as a totally unexpected voice bawled, "Shut up, you Froggie gasbag - I can't understand a flaming word you've been jabbering," and then I realised that I had been unwittingly riding with Bainbridge." - Sir Hubert Opperman on the 1931 Tour

In

1937, there were 20 stages. Three of them - 5, 14, 17 - were split into parts A, B and C, Stages 11, 12, 13, 18 and 19 were split into Stages A and B; and they covered a total of 4,415km.

Since the Tour began, Henri Desgrange had allowed only wooden wheel rims for fear that the heat generated on the descents would melt the glue holding tubular tyres to metal rims - which were first permitted in this edition. For the very first time, a British team took part: Bill Burl and Charles Holland were the first British riders to enter the race and they were joined by a Canadian, Pierre Gachon, who was the only non-European (Gachon abandoned in Stage 1, Burl went in Stage 2 after being knocked off by a photographer and breaking his collarbone, Holland eventually went in 14c but had ridden well). The Italian team returned, Mussolini having banned Italian cyclists from entering in 1936. Among them was Gino Bartali, making his Tour debut: he fell into a river during Stage 8 and was very nearly swept away by the current - thankfully, Francesco Camusso was nearby and managed to grab hold of him and haul him out. He continued, but lost significant time in the next stages and abandoned in Stage 12.

|

| Roger Lapébie |

Roger Lapébie, who was one of the few riders on a bike equipped with a derailleur (which had just been permitted in the race for the first time since 1912 - see above) was elected leader by the remaining six riders from the French team at the start of Stage 9 but, at the start of Stage 15 was the victim of sabotage when his handlebars were partially sawn through. He managed to bodge a repair, but his bike hadn't been fitted with a bidon cage and he came very close to giving up in that stage until a team mate persuaded him to continue - after Sylvère Maes punctured, Lapébie was able to take second place and won a 45" time bonus, but then lost it when officials found he'd been pushed by spectators and penalised him 90". The Belgians thought that be should have been punished more severely, but the French team threatened to leave en masse if this happened and no further action was taken.

In Stage 16, Maes punctured again and was helped back into the lead by Adolf Braeckeveldt and Gustaaf Deloor - both were Belgian, but they were touriste-routiers rather than part of the Belgian team and so their assistance should not have fallen foul of the law that riders could not be helped by members of their own team. Nevertheless, Maes was penalised 15". Earlier in the stage, the gate at a railway crossing had been lowered right after Lapébie had gone through and just as Maes was about to follow him. The Belgian team believed this had been done deliberately and, adding a complaint that the French fans threw stones at them, they left the race.

From that point onwards, Lapébie was without challenge and had little difficulty in winning. This edition was marred by an unwelcome, ugly sight - the swastika-emblazoned jerseys of the team from Nazi Germany.

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Roger Lapébie (FRA) France 138h 58' 31"

2 Mario Vicini (ITA) Individual[1] +7' 17"

3 Leo Amberg (SUI) Switzerland +26' 13"

4 Francesco Camusso (ITA) Italy +26' 53"

5 Sylvain Marcaillou (FRA) France +35' 36"

6 Edouard Vissers (BEL) Individual +38' 13"

7 Paul Chocque (FRA) France +1h 05' 19"

8 Pierre Gallien (FRA) Individual +1h 06' 33"

9 Erich Bautz (GER) Germany +1h 06' 41"

10 Jean Frechaut (FRA) Individual +1h 24' 34"

|

| Bartali in the mountains, 1948 |

The

1948 Tour was second edition since the Second World War, and it consisted of 21 stages covering a total of 4,922km. When the 1947 Tour took place, the conflict had come to an end but the peace treaty between France and Italy had not yet been signed. This meant that, legally, the two nations were still at war, so the Italian team had to be made up of Italians resident in France. In 1948 the situation had been resolved and Bartali was back.

For the very first time, a stage was broadcast live on television and millions of people across the nation tuned in to watch the riders cross the last finish line at the Parc des Princes velodrome. The TV cameras attracted new sponsors, most notably the Les Laines woolens company which became the new sponsor of the maillot jaune, and introduced financial rewards for those who got to wear it. In 1947, newspapers had complained that too many riders rode deliberately slowly in an attempt to become lanterne rouge - while this guaranteed them more media attention and race invites than finishing anywhere else outside the top ten (even anywhere other than first place, if they had good business sense), it was felt that it made the race boring. The public wanted a return to the days of old when heroic riders risked life and limb to be faster than their rivals, thus a new rule stated that the last rider over the line in Stages 3 to 18 would be eliminated from the race.

The Tour organisers had invited the Swiss to send a team, largely because they wanted the crowd-pleasing Tour de Suisse winner Ferdi Kübler in the race, but Kübler refused because he could make more money winning several small races than entering one big one that he probably wouldn't win. However, the Swiss Aeschlimann brothers Roger and Georges, who came from Lausanne and thus guaranteed a good crowd turn-out when the race visited the city at the end of Stage 15, did want to come. They were immediately accepted and placed into a team with eight foreign-born French residents which became known as The Internationals.

The Italian team had argued before the race over whether Bartali or Fausto Coppi, who had already won two Giri d'Italia, should be team leader. The Tour organisers wanted both men in the race and even permitted a second Italian team so they could both lead, but eventually Coppi decided to sulk and refused to take part at all. Bartali was no longer a young man and whilst the war had taken its toll on everyone, he didn't look to be in good shape (nobody knew it yet, but it had taken a greater psychological toll on him than on many others - he'd spent much of it risking torture and execution at the hands of the Fascists by personally smuggling Jewish Italians to safety in neutral Switzerland). He won the first stage, but then began to struggle and Louison Bobet had little trouble in gaining the overall lead and keeping it - though he collapsed after Stage 11, he recovered in time to win the next day.

After finishing Stage 12 with an overall disadavantage of 20', Bartali told his team mates that he was going to abandon; but they persuaded him to sleep on it and see how he felt the following day. He did so, but during the night was woken by a phonecall from Alcide De Gasperi - the prime minister of Italy. De Gasperi told him that Palmiro Togliatti, chairman of the Communist Party, had been assassinated. Could Bartali try his very best to win the next day, he asked, in the hope that such good news might prevent the populace rising up and thrusting the country into civil war?

Bartali assured him that not only would he win the stage, he would win the race - and he kept both promises. Stage 13 was won with a 6'13" lead after he took on and beat no less a rider than Briek Schotte (whom many of the toughest riders of Flanders say was the only true Flandrien), reducing the gap between himself and Bobet to 1'06". Then he won Stages 14 and 15 too, which gave him an overall lead of 1'47" - and, more importantly, united Italy in their support for him. He finished 32" behind stage winner Edward van Dijck in Stage 16, but because his rivals lost significant time his overall lead grew to 32'20" and from that point onwards. Ten years after his first Tour victory, he had won another - the longest period between two wins by any one individual in the history of the race.

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Gino Bartali (ITA) Italy 147h 10' 36"

2 Brik Schotte (BEL) Belgium +26' 16"

3 Guy Lapébie (FRA) Centre-South East +28' 48"

4 Louison Bobet (FRA) France +32' 59"

5 Jeng Kirchen (LUX) NeLux +37' 53"

6 Lucien Teisseire (FRA) France +40' 17"

7 Roger Lambrecht (BEL) Internationals +49' 56"

8 Fermo Camellini (ITA) Internationals +51' 36"

9 Louis Thiétard (FRA) Paris +55' 23"

10 Raymond Impanis (BEL) Belgium +1h 00' 03"

1949

|

| Fausto Coppi |

21 stages, 4,808km.

Once again, the Italian team was split by a row over whether Bartali or Coppi should win. Since Bartali had won the previous year and was considered more experienced, he was chosen - but, after considering leaving the race due to lack of support, this time Coppi won.

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Fausto Coppi (ITA) Italy 149h 40' 49"

2 Gino Bartali (ITA) Italy +10' 55"

3 Jacques Marinelli (FRA) Ile de France +25' 13"

4 Jean Robic (FRA) West-North +34' 28"

5 Marcel Dupont (BEL) Belgian Aiglons +38' 59"

6 Fiorenzo Magni (ITA) Italian Cadets +42' 10"

7 Stan Ockers (BEL) Belgium +44' 35"

8 Jean Goldschmit (LUX) Luxembourg +47' 24"

9 Apo Lazaridès (FRA) France +52' 28"

10 Pierre Cogan (FRA) West-North +1h 08' 55

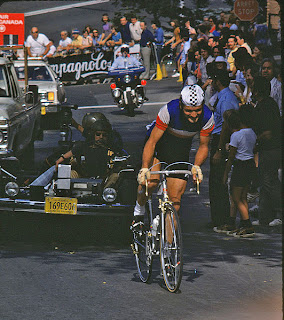

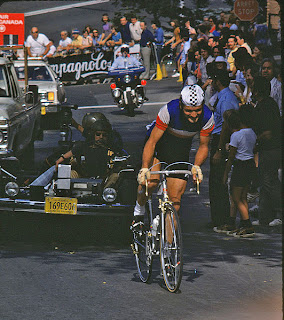

|

| Cyrille Guimard |

In 1973 there were 20 stages, Stages 1, 2, 7, 12, 16 and 20 being split into parts A and B. The total distance covered was 4,140.4km. Before the route was announced, there were widespread grumblings that the organisers had plotted out a much flatter parcours than usual in an attempt to favour Cyrille Guimard - once, it had been an open secret that French riders received preferential treatment, but when the race details were revealed and it turned out that in actual fact three more mountains had been added it was seen that those days had come to and end. This is less indication that the organisers had made a conscious decision to be more fair and more a sign that the Tour had now grown so big that it transcended Frenchness; it was now a world event.

For once, there were no major changes to the rules; the biggest difference from 1972 being the absence of Eddy Merckx - he had switched from Faema to the Molteni team with a contract to ride the Vuelta a Espana (26th April-13th May) and the Giro (18th May-9th June), and even he didn't much fancy the idea of three Grand Tours totaling more than 11,000km in the space of just under three months. No French riders took part in the 1973 Giro, which was thought to be a slight and so no Italian teams came to the Tour.

|

| Luis Ocaña, seen in 1971 |

Raymond Poulidor was a favorite, chosen by the heart more than the head - he was no longer a young man, but after so many years in the shadow of first Anquetil and then Merckx his legions of fans hoped that be might somehow take the Tour victory he'd wanted for so long. Bernard Thévenet and José-Manuel Fuente were reckoned to be in with a good chance too; but the man deemed by far most likely to win was the Spaniard Luis Ocaña, who had come very close to preventing Merckx from taking his third victory in 1971. He and Herman van Springel crashed in Stage 1a after a dog ran across the road in front of them, but neither man was hurt (they both managed to avoid the dog, too). Ocaña joined Guimard in a two-man break in Stage 3 and succeeded in putting two minutes between himself and Zoetemelk, but probably felt far more pleased with his new 6' lead over José-Manuel Fuente because the two men hated each other. Their enmity was not helped at all during Stage 8, when they attacked at the same time and ended up riding together over Izoard: Fuente stopped doing his share of the work near the top, then sprinted past to take the best points. Now that they were trying to outdo one another, their pace kept rising higher and higher - eventually Fuente punctured and, some would say quite rightfully considering what had happened on Izoard, Ocaña attacked; crossing the finish line alone with a lead of 58". The next riders after Fuente arrived nearly seven minutes later, but the peloton was more than twenty minutes down the road.

At the end of Stage 9, British rider Barry Hoban failed an anti-doping control, was fined 100 Swiss Francs and was eliminated from the race. Hoban had been a close friend of Tom Simpson, who died six years and one day earlier on Mont Ventoux when the amphetamines he took prevented him from knowing that his body could take no more, and two years after that he married Simpson's widow. That he of all people was still willing to dope shows that for the majority of riders doing so really was a necessity simply in order to be able to keep up at that time.

Poulidor lost control during Stage 13 and plunged into a ravine on Portet d'Aspet. With help - including race director Jacques Goddet - he was able to climb back up to the road, but had injured his head and had to be helicoptered to hospital. Fans prayed for his recovery, but nobody really thought his chances of winning had ended that day - Ocaña had led since Stage 7a, and his victory hadn't really been in any doubt for some time. When it came, he was able to say he'd earned it; but it can't have tasted as sweet as one against Merckx.

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Luis Ocaña (ESP) Bic 122h 25' 34"

2 Bernard Thévenet (FRA) Peugeot +15' 51"

3 José-Manuel Fuente (ESP) Kas +17' 15"

4 Joop Zoetemelk (NED) Gitane +26' 22"

5 Lucien Van Impe (BEL) Sonolor +30' 20"

6 Herman Van Springel (BEL) Rokado +32' 01"

7 Michel Périn (FRA) Gan +33' 02"

8 Joaquim Agostinho (POR) Bic +35' 51"

9 Vicente Lopez-Carril (ESP) Kas +36' 18"

10 Régis Ovion (FRA) Peugeot +36' 59"

1977

(Bernard Thevenet)

|

| Bernard Thevenet |

22 stages (Stages 5, 7, 13, 15 and 22 split into parts A and B) + prologue. 4,096km

The Giro d'Italia and Vuelta a Espana paid teams to take part but the Tour, being the grandest of the Grand Tours, expected teams to pay for the honour. In 1977, several teams chose t stay away, either in protest or because they were unable to afford the fee - for that reason, the unusually low figure of 100 riders started. Lucien van Impe, winner in 1976, was hoping for a second victory and remained a favourite right up until the route was announced. However, after several years in which the mountain stages had dominated the race the organisers had decided to put more emphasis on the time trials; Bernard Thévenet, who had ended the reign of Merckx in 1975, took over. Joop Zoetemelk, Hennie Kuiper and Raymond Delisle were expected to give him problems. Merckx was there, but was far past his best and many people wondered what had become of his promise to quit while he was ahead. Dietrich Thurau, riding the Tour for the first time, won the prologue and dreamed of wearing the maillot jaune for Stage 13 when the race visited Germany; unfortunately the Pyrenees came early in 1977, starting in Stage 2 and threatening to ruin his chances. However, after teaming up with Merckx he managed to remain in contention and then won back time during the time trials - he got his wish. The riders got bored during the nine stages between the Pyrenees and the Alps, which began in Stage 14, and as result the race became boring. Jacques Goddet published a report, really an angry open letter to them, in L'Equipe in which he attacked them for their apathy. Surprisingly, they didn't threaten to strike. Agostinho won Stage 18 but then failed an anti-doping test, so the win was disallowed. Antonio Menendez from KAS was thus declared winner, but then he failed a test too. Merckx had been third, but he hadn't been tested and by now it was too late - so the stage still has no official winner. Thévenet had no problems in the last stages and took his victory unchallenged - it had been an interesting Tour, but for all the wrong reasons.

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Bernard Thevenet (FRA) Peugeot 115h 38' 30"

2 Hennie Kuiper (NED) Raleigh +0' 48"

3 Lucien Van Impe (BEL) Lejeune +3' 32"

4 Francisco Galdos (ESP) KAS +7' 45"

5 Dietrich Thurau (GER) Raleigh +12' 24"

6 Eddy Merckx (BEL) Fiat +12' 38"

7 Michel Laurent (FRA) Peugeot +17' 42"

8 Joop Zoetemelk (NED) Miko +19' 22"

9 Raymond Delisle (FRA) Miko +21' 32"

10 Alain Meslet (FRA) Gitane +27' 31"

1990

21 stages + prologue, 3,404km

The Combination and Intermediate Sprint Classifications vanished from the race, neither has since been reintroduced. Greg Lemond took his third victory, a remarkable recovery after he was nearly killed when a dropped shotgun fired 40 pellets into his back.

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Greg LeMond (USA) Z 90h 43' 20"

2 Claudio Chiappucci (ITA) Carrera Jeans-Vagabond +2' 16"

3 Erik Breukink (NED) PDM +2' 29"

4 Pedro Delgado (ESP) Banesto +5' 01"

5 Marino Lejarreta (ESP) ONCE +5' 05"

6 Eduardo Chozas (ESP) ONCE +9' 14"

7 Gianni Bugno (ITA) Chateau d'Ax +9' 39"

8 Raúl Alcalá (MEX) PDM +11' 14"

9 Claude Criquielion (BEL) Lotto-Superclub +12' 04"

10 Miguel Indurain (ESP) Banesto +12' 47"

Cyclists born on this day: Jackson Stewart (USA, 1980); Geoffrey Lequatre (France, 1981); Wayne McCarney (Australia, 1966); Léon Gingembre (France, 1875, died 1928); Valentino Gasparella (Italy, 1935); Rocco Travella (Switzerland, 1967); Luděk Štyks (Czechoslovakia, 1961); Karl Koch (Germany, 1910, died 1944); Anthony Stirrat (Great Britain, 1970); Joona Laukka (Finland, 1972); Gaynan Saydkhuzhin (USSR, 1937); Corine Dorland (Netherlands, 1973); Kjell Rodian (Denmark, 1942); Ignacio Gili (Argentina, 1971); Kashi Leuchs (New Zealand, 1978); Diego Garavito (Colombia, 1972); Lucjan Józefowicz (Poland, 1935); Sylvain Chavanel (France, 1979).

Henri Desgrange versus the Mercier bicycle company

In 1934, André Leducq broke his contract with the Alcyon team and went to ride for Mercier (money was involved, as was team owner Émile Mercier's offer to rename the team A. Leducq-Mercier-Hutchinson). Alcyon boss Edmond Gentil was not at all happy so, knowing that Desgrange personally chose the riders for the French national team, he asked him not to select Leducq. Desgrange agreed.

Mercier heard what had happened and began to complain, writing numerous letters to the paper and eventually getting his lawyers involved. Desgrange, as usual, expected any decision he made to be final and go without questioning, so he ordered the staff at his L'Auto newspaper (which ran the Tour) to never mention Mercier again, either in the offices or in print. Mercier was now even more angry, but still Desgrange ignored him. However, since Mercier sponsored a successful team and was an important manufacturer, it became increasingly difficult not to mention them - so Desgrange found a compromise: from that point onwards, the team could be mentioned in the paper but had to be spelled wrongly. Mercier was now absolutely apoplectic with rage and fired off a stiffly-worded complaint each and every time it happened.

The first time, Desgrange printed an apology. ""Monsieur Gercier has let us known that his name is Monsieur Mervier," it read. Another complaint soon followed. This time, the apology read: "Monsieur Mervier asks us to say that, in reality, he is called Monsieur Cermier." The next complaint was even more angry. Desgrange's response? "Monsieur Cermier insists that in fact he is known as Monsieur Merdier."

Desgrange is also frequently said to have stolen all the credit for the Tour from his employee Geo Lefévre, the man who supposedly thought it up completely off-the-cuff at a L'Auto crisis meeting in 1902. To find out why this accusation may be unjust, click here.

.jpg)