1907

|

| Stage 3, 1907 |

In any Tour, the winner of the last edition is usually considered the favourite; in 1907 René Pottier could not be due to tragic circumstances - some time around Christmas and the New Year, he'd discovered that while he was away winning the 1906 Tour his wife had been having an affair and, on the 25th of January, he hanged himself. Louis Trousselier, Emile Georget and François Faber were considered most likely to replace him and, for the first time, favourites achieved something like modern celebrity status with newspapers and magazines publishing biographies, back stories and gossip. For the second time, the race ventured outside France - in 1906 it had gone into German-controlled Alsace-Lorraine, it did so again when it visited Metz but under notably different conditions: with relations between Europe's great powers deteriorating fast, the French flag was strictly banned once the race passed the border and the official cars were not permitted to go with the riders. Curiously, one of the biggest problems was caused on the way back into France - French customs held the riders up for so long that the race had to be halted and restarted once they'd finished. During Stage 4 from Belfort to Lyon, the race passed through Romandy - the first time it had ever been to Switzerland. It was also the first time that the Alps were specifically included for the challenge they presented, rather than simply because they happened to be between stage towns, Henri Desgrange having been persuaded by the popularity of the Vosges and Massif Central stages in the previous two years that his fears the riders would be attacked by bandits or eaten by bears was worth the risk. Because of this added hardship, the coureurs de vitesse (riders sponsored by trade teams, but expected to ride for themselves alone) were permitted to receive help from mechanics following the race in cars and could even continue on a replacement bike if their machine was declared beyond repair by a course official. Coureurs sur machines poinçonnées (later known as touriste-routiers and then independents before being barred from entry) received either limited sponsorship, perhaps being supplied with a bike, or none at all and were expected to carry out all repairs themselves and to complete the race with only one bike.

|

| Georget's crash, 1907 |

During Stage 9, Georget arrived at a checkpoint where riders had to stop and sign their names to prove they'd followed the route and not taken shortcuts (or, as was quite common in the early Tours, a train), and just as he arrived his frame snapped. What happened next is slightly mysterious: despite the race officials around the checkpoint meaning that any sort of rule-breaking would be spotted and punished, he decided that rather than losing time by waiting while his damaged bike was declared irreparable he'd just take one from his Peugeot-Wolver team mate Pierre Gonzague-Privat, who was so far behind overall that waiting for a decision and a replacement made little difference - was he completely ignorant of the rule, did he think that it would be overlooked (and anyone who knew anything about Tour officials and their legendary officiousness would surely be well aware that it would most definitely not) or was he told by an unknown person, perhaps an official bribed by another rider or team manager, that he could take his team mate's bike? More than a century later, we will probably never know. He was fined 500 francs, but ended with a 19.5 point advantage over Lucien Petit-Breton who moved into second place by winning the stage.

|

| At Ville d'Avray, 1907 |

|

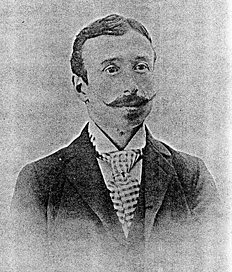

| Lucien Petit-Breton |

The majority of coureurs sur machines poinçonnée were poor and would sleep anywhere they could during the race, often spending the night in a barn or, sometimes, in a hedge; they would also eat whatever they could find along the way - in those days, when many of them would have been used to living as peasants, they'd have been adept at catching rabbits and birds and foraging for edible plants but they also sometimes lived on what the sponsored riders discarded (as happened in 1914, when a hungry poinçonnée eagerly pounced upon and devoured a half-eaten sandwich thrown away by a sponsored rider - who was promptly penalised by officials for providing assistance to a rider that wasn't part of his own team). Some, meanwhile, were wealthy men who entered the Tour for the adventure - and the most famous of them all was Henri Pépin. Pépin had no intention of winning the Tour and treated it all as a jolly jaunt around the countryside, taking with him a pair of men named Henri Gauban and Jean Dargassies (actually Dargaties, but Tour organisers misheard him and it stuck) whom he had hired to support him and act as manservants (and who, as a result, are the first riders to have ridden a Tour purely to support another rider rather than to attempt a win for themselves - the first domestiques, no less). Each night, at his expense, they slept in the finest hotel the stage town had to offer and every day they would select a restaurant along the route and dine in style. They were, therefore, far from the first riders over the line every day; in fact, they finished Stage 2 twelve hours and twenty minutes after winner Emile Georget, the more serious riders having set off at 5.30am while Pépin was engaged in what journalist Pierre Chany delicately termed "conversation with a lady" - they were not, however, last; four men finished after them. By all accounts, Desgrange was not impressed, but as the race was decided on points rather than times (hence no time limits) there was nothing he could do.

|

| Henri Pépin |

"Nonsense!" Pépin told him, instructing Gauban and Dargassies to pull the man out of the ditch. "We are but three but we live well and we shall finish this race. We may not win, but we shall see France!" The three were now four, with Pépin happily paying for Teychenne to get a taste of the highlife with them.

In Stage 5, Pépin decided he'd had enough of the game and paid his assistants a sum equal to the prize awarded to the race winner, then caught a train home. Dargassies - who, it appears, knew Pépin from the 1905 Tour which they had both ridden - went with him while Gauban elected to continue and did rather well for a while, narrowing the enormous gap between himself and the race leader to just 36 minutes, but was then beset by misfortune and abandoned during Stage 11. He had entered every Tour since it began, but this was his last. Dargassies also never entered again, but Pépin returned at the age of 49 and raced again in 1914, the year that he died of what was then termed "athleticism" - probably a coronary caused by an undetected heart defect.

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Lucien Petit-Breton (FRA) Peugeot-Wolber 47 Poinçonnées

2 Gustave Garrigou (FRA) Peugeot-Wolber 66 Vitesse

3 Emile Georget (FRA) Peugeot-Wolber 74 Vitesse

4 Georges Passerieu (FRA) Peugeot-Wolber 85 Vitesse

5 François Beaugendre (FRA) Peugeot-Wolber 123 Poinçonnées

6 Eberardo Pavesi (ITA) Otav 150 Poinçonnées

7 François Faber (LUX) Labor-Dunlop 156 Poinçonnées

8 Augustin Ringeval (FRA) Labor-Dunlop 184 Vitesse

9 Aloïs Catteau (BEL) – 196 Poinçonnées

10 Ferdinand Payan (FRA) – 227 Poinçonnées

1954

23 stages (Stages 4 and 21 split into parts A and B), 4,656km.

|

| Wagtmans, 1954 |

Bobet had won Stage 2, but the Swiss riders Ferdy Kübler and Hugo Koblet were right behind him: Koblet, who had won in 1951, was only a minute down in the General Classification at the end of the stage and Gilbert Bauvin just 30". However, it was early days yet and Bobet was a wise rider; he had, therefore, no intention of taking the lead just yet as defending it would require energy best saved for later on - and was probably quite surprised that the maillot jaune remained his when he finished outside the top ten for Stages 4b (during which the strange little climber Jean Robic collided with a photographer and abandoned the race) and 5, then ninth on Stages 6 and 7. In fact, it took until Stage 8 before Wagtmans managed to get into a breakaway and made up enough time to win it back.

|

| Bahamontes on Tourmalet, 1954 |

|

| Ferdinand Kübler |

|

| Bobet on Izoard |

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Louison Bobet (FRA) France 140h 06' 05"

2 Ferdi Kübler (SUI) Switzerland +15' 49"

3 Fritz Schär (SUI) Switzerland +21' 46"

4 Jean Dotto (FRA) South East +28' 21"

5 Jean Malléjac (FRA) West +31' 38"

6 Stan Ockers (BEL) Belgium +36' 02"

7 Louis Bergaud (FRA) South West +37' 55"

8 Vincent Vitetta (FRA) South East +41' 14"

9 Jean Brankart (BEL) Belgium +42' 08"

10 Gilbert Bauvin (FRA) Center-North East +42' 21"

Cyclists born on this day: Jesse Sergent (New Zealand, 1988); Smaisuk Krisansuwan (Thailand, 1943); Christel Ferrier Bruneau (France, 1979); Mark Bristow (Great Britain, 1962); Jenny McCauley (Ireland, 1974); Otto Luedeke (USA, 1916, died 2005); James Jackson (Canada, 1908); Roberto Pagnin (Italy, 1962); Werner Karlsson (Sweden, 1887, died 1946); Paolo Tiralongo (Italy, 1977); Ivonne Kraft (West Germany, 1970); Bärbel Jungmeier (Austria, 1975); Bernard van de Kerckhove (Belgium, 1941); Stefano Colage (Italy, 1962); Jean-René Bernaudeau (France, 1956); Sven Johansson (Sweden, 1914, died 1982); Bill Messer (Great Britain, 1915); Serge Proulx (Canada, 1953).