The Tour de France started on this date in 1908 and 1950 - the latest Tours in history.

Tour de France 1908

|

| Le Grand Depart, 1908 |

Using an almost identical route to 1907, the 1908 edition had one notable difference to previous years: all cyclists were in the same classification and they all rode identical yellow frames issued to them by the race, though they were still permitted to choose some components for themselves - one popular option was clincher tyres which, while not as efficient as tubular tyres, made repairing punctures considerably easier; since riders were required to carry out all maintenance and repairs themselves this was an important consideration. 36 riders were using them, the majority of which were made by Wolber (who also co-sponsored the Peugeot team) - those riders became eligible for the secondary and unofficial "Prix Wolber pneus démontables" classification, which offered a prize of 3,500 francs to the first rider over the finish line on a bike fitted with them and brought a huge amount of public and media attention for both the product and the manufacturer. Organisers also promised that steps had been taken to prevent bad behaviour and sabotage by spectators, who in the past had done everything from spread nails over the road to forming mobs and physically beating the riders; this year, the riders were reassured, there was a 90% chance that what was termed "the Apaches" would be apprehended by the police and go to prison.

|

| Marie Marvingt |

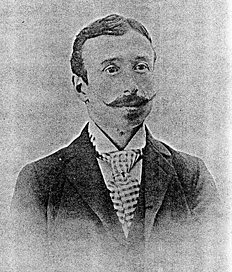

No cyclist had ever won two Tours (with the exception of Maurice Garin, whose second victory was disqualified due to cheating), but Lucien Petit-Breton believed that he could and he planned to do so; being the first man to centre his entire season on this one race alone (that he would so is indication that, five years after it began, the Tour was already the most important bike race in the world). Using other events solely to train and caring little where he placed in them, he artfully ensured that he reached a peak of physical fitness for the Tour - something that had never before been done and which would not be used again until Miguel Indurain's five wins between 1991 and 1995 and Lance Armstrong's seven wins between 1999 and 2005. What's more, Petit-Breton (whose real surname was Mazan; he had become known as Lucien Breton at the start of his career when he lived in Argentina and began to use it so that his father - who wanted him to get a "proper" job - wouldn't recognise his name in the race results published in newspapers, the Petit being added because there was another rider named Lucien Breton) had the very strong Peugeot team backing him up and, crucially since riders had to carry out their own repairs, he was a skilled mechanic.

|

| Passerieu and fans at the Tour, 1908 |

Stage 2 ended and Stage 3 began in Metz, which as part of the Lorraine region was then under German control. Desgrange, like many Frenchmen, saw the German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine as an insult to his country it seems strange that he would steer his race through the region; however, one of the reasons he organised the race in the first place was to show off the strength and athleticism of France's young men, he probably welcomed it as an opportunity to demonstrate to Germany that should they ever get ideas about expanding their territory further onto French soil they'd be met by formidable resistance. He was probably pleased, therefore, that Stage 3 was started by none other than the Count von Zeppelin: while no longer a General in the German army (he'd been forced to retire after his command came under heavy criticism in 1890), he retained great power and influence. During the stage Jean Novo, riding for the Labor team, crashed and had to retire. The team's owner then sent a telegram to the manager ordering him to withdraw the team on account of its "mediocre results." Labor is notable in that the riders wore bright yellow jerseys, which stood out in the peloton and made them easy to recognise - this may very well have been where Desgrange got the idea for the maillot jaune which he would later reserve for the leader of the race (we know for certain that the race leader wore a yellow jersey in 1919, but late in his life Philippe Thys said that he'd been given one when he led in 1913 - nobody can prove that he was, but nobody can prove he wasn't either). With Labor gone and Alcyon unable to achieve the performances they would in the coming years, Peugeot dominated the race from that point onwards; beginning with François Faber's Stage 3 victory (while Faber considered himself to be French, he a Luxembourgian passport and was the first Luxembourgian - and only the second foreigner - to win a Tour stage). Petit-Breton finished with him and thus remained in the lead with five points.

|

| Faber, who later died in No Man's Land when he tried to rescue an injured comrade |

Stage 10 went to Georges Paulmier - Petit-Breton was tenth, by far his worst performance in the race as he finished top four on every other stage. His lead was too great to be threatened, falling to 32, but Faber was only one point ahead of Passerieu and would need to work hard to remain in contention for second place. Petit-Breton won Stage 11, adding two points to his advantage; Faber and Passerieu both had 63 points after the stage but Faber remained officially in second place (which suggests that Passerieu was probably declared sole leader following Stage 2), then secured his position in Stage 12 by opening a gap of five points. It took Passerieu 16h23' to win Stage 13, the longest in the race at 415km; Faber was second and Petit-Breton third, the three of them finishing together - the last rider to complete the stage, Louis di Maria, needed an extra 23h07' to arrive at the finish line.

|

| Lucien Petit-Breton |

Faber may have been second, but he was declared winner of the Prix Wolber. When the 3,500 francs were added to the prize money he earned for second place in the General Classification, he ended up making more money from the race than Petit-Breton did; however, Petit-Breton later wrote a book, Comment je cours sur route (How I Race on the Road), which is half-memoir and half the earliest example of a cycling training manual.

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Lucien Petit-Breton (FRA) Peugeot–Wolber 36

2 François Faber (LUX) Peugeot–Wolber 68

3 Georges Passerieu (FRA) Peugeot–Wolber 75

4 Gustave Garrigou (FRA) Peugeot–Wolber 91

5 Luigi Ganna (ITA) Alcyon–Dunlop 120

6 Georges Paulmier (FRA) Peugeot–Wolber 125

7 Georges Fleury (FRA) Peugeot–Wolber 134

8 Henri Cornet (FRA) Peugeot–Wolber 142

9 Marcel Godivier (FRA) Alcyon–Dunlop 153

10 Giovanni Rossignoli (ITA) Bianchi 160

(Note: with Peugeot's domination of the race so complete, the identical bikes experiment - which had previously applied only to the second-class riders rather than to the entire field - was considered unsuccessful and dropped. However, in 1909 bikes still had to be fitted with a stamped lead seal by organisers to make sure riders didn't illegally change bikes during the race.)

Tour de France 1950

22 stages, 4,775km.

Aware that some riders broke the rules by receiving a helpful push from team staff as they collected fresh bidons, organisers announced that course officials would be keeping a close eye on things and that there would be harsher penalties for any rider spotted breaking rules in this way. There had also been concerns that the bonification system gave climbers an unfair advantage over other riders, thus this was overhauled: being the first to a summit now earned a bonus of 40" rather than a minute and no new mountains were added to the parcours. Prizes increased - a stage winner would now receive 50,000 francs, an increase of 20,000f when compared to 1949, and the overall General Classification winner would receive 100,000. Since stages were now on average much shorter than they had been in the early days of the Tour, cut-off times were reduced dramatically and, for the first time, French TV broadcast live coverage of every stage. In addition to the national and French regional teams, the plan to include an international team gradually developed into one for a North African team consisting of riders from French-controlled Algeria and Morocco.

|

| Gino Bartali |

Orson Welles was given the honour of starting the first stage, which was won by the Luxembourgian rider Jean Goldschmidt. He then retained the maillot jaune through Stage 2 before Bernard Gauthier finished sixth in a seven-strong break on Stage 3, ending up with 5" overall advantage. Gauthier wasn't considered able to keep it but then did, finishing in sixth place again on Stage 4 to increase it to 2' which remained intact despite his 21st place on Stage 5. Meanwhile, Kübler had finished top ten on the first two stages and ended Stage 5 4'30" down in 9th overall, but he knew he was going to do well in the Stage 6 individual time trial. In fact, he did very well and beat Fiorenzo Magni by 17" and all his rivals by at least 2'55", jumping to third overall with a disadvantage of only 49" - which would have been even greater had be not have decided to stop and change his jersey on the parcours, picking up a 25" penalty for doing so (some sources say that this is incorrect and he was penalised 15" and fined 1,000 francs for wearing a silk jersey rather than a regulation woolen one; while there are obvious advantages to a silk rather than woolen jersey in a time trial, the harshness of time and financial penalty seem so wildly at odds with one another that the first version appears more plausible). Gauthier got away in a successful break again the next day (when Kübler was fined, 100 francs for turning up late at the start line; later in the race he was fined again for getting a push from fans): while he was 11th over the line, the break had been made up of riders far down in the General Classification and he finished with the yellow jersey and an overall advantage of 9'20". Although there was still two weeks of racing to go, a good all-rounder might have been able to defend a lead such a that all the way to the end if he had luck on his side, but Gauthier was not a climber. The favourites didn't even bother trying to take back time over the next few stages, allowing him to keep the jersey and his advantage. Then the race arrived at the Pyrenees and he came 53rd behind Bartali; just like that his huge lead turned into a 9'49" disadvantage and he dropped to 12th overall - he would never wear the maillot jaune again.

|

| Jean Robic |

We will never know the truth but, whatever really happened Bartali was sufficiently shaken to announce that he wouldn't be continuing with the race and, as team leader, the majority of the Italians said that they would go with him. Some wanted to stay and help Magni defend the 2'31" advantage with which he finished the stage, but Magni - who, despite holding political beliefs so right-wing he was despised by most other riders, respected the elder statesman of Italian cycling - revealed he was going too, thus becoming the fourth man in history to abandon the Tour while wearing the yellow jersey. Race organisers tried to encourage them to continue by offering them plain grey jerseys so that they'd be less recognisable, but it was to no avail and both the Italian A and B teams abandoned.

Kübler now became overall leader with a 3'20" advantage over Bobet, but he refused to wear the maillot jaune in Stage 12 to acknowledge the fact that it was his by default. The stage was won by a Belgian, Maurice Blomme, and it would be the only Tour stage win of his career. Getting there took so much out of him that he mistook a shadow on the road for the finish line and got off his bike; fortunately a race official was on hand to get him back on his bike and explain he had a few more metres still to go.

|

| Abdel-Kaader Zaaf asleep under the tree |

The weather remained the same for the next few days and nobody could really be bothered to starting working on Kübler's 1'06", considering it small enough to easily be dealt with later in the race. During Stage 15, the peloton as one came to the decision that it was much too hot for cycling, so they stopped, got off and went for a cooling swim in the Mediterranean. Director Jacques Goddet was furious and ordered them to get on with the race immediately or be disqualified - unfortunately, reporters found the incident hilarious and he was unfavourably portrayed in the newspapers the next day; he got his revenge by fining all the riders. Stage 16 brought more drama: Kübler won with the Belgian Stan Ockers and Bobet taking second and third right behind him, but the judges declared Bobet to be second despite even the French fans insisting he was third, and the Belgian team threatened to leave the race if things were not put right. The judges ignored the threat and refused to change the result, and the Belgians eventually backed down and continued.

By the end of Stage 18, during which Bobet tried to win back time on Izoard, the mountain where he would win the Tour in the future, Kübler's lead had increased to 2'56" and he added another 30" the next day when he finished second, 34" behind Geminiani. It was now beginning to look very much as though he might win, especially with the Stage 20 mountain time trial still to go. He more than lived up to expectations that day, beating Ockers by 5'34" and Bobet by 8'45"; his overall lead going into the final two plain stages was 9'30" on the Belgian and 22'19" on the Frenchman. It wasn't really worth their while trying to claw it back from that point onwards, and so 9'30" was the winning margin for the first Swiss rider to win the Tour de France.

There were many, of course, who said that had Coppi been there or the Italian teams have stayed in the race, Kübler would not have won. Coppi may indeed have won if he wasn't at home with a broken pelvis; but he was and that's how cycling works, so that point is irrelevant. Bartali, as already described, was past his best and coming to the end of his career - he had been one of the greatest Tour riders ever seen and was still capable of beating far younger men in the mountains, but in this edition the time trials counted for a great deal and he wasn't as fast as he once was. Magni, meanwhile, was a superb rider in the flat time trials, as can be seen by his second place finish in Stage 6 when he was only 17" behind Kübler; but he wasn't much of a climber. However, Kübler could climb and time trial, so it seems that his insistence that he'd have won regardless is probably correct.

At the time of writing, summer 2012, Kübler is 92 years old and the oldest living Tour de France winner.

Top Ten Final General Classification

1 Ferdi Kübler (SUI) Switzerland 145h 36' 56"

2 Stan Ockers (BEL) Belgium +9' 30"

3 Louison Bobet (FRA) France +22' 19"

4 Raphaël Géminiani (FRA) France +31' 14"

5 Jean Kirchen (LUX) Luxembourg +34' 21"

6 Kléber Piot (FRA) Ile de France–North East +41' 35"

7 Pierre Cogan (FRA) Center–South West +52' 22"

8 Raymond Impanis (BEL) Belgium +53' 34"

9 Georges Meunier (FRA) Center–South West +54' 29"

10 Jean Goldschmit (LUX) Luxembourg +55' 21"

The Death of Tom Simpson

|

| Tom Simpson 30.11.1937 - 13.07.67 |

Simpson did not die in vain: his death was the wake-up call that alerted the world to the prevalence and dangers of doping and forced organisers to begin to consider ways to control it.

La Flèche Wallonne was not held in the wake of the 1940 Nazi invasion and occupation of Belgium, and so the edition held on this day in 1941 - the fifth - was the first time the race had taken place for two years. Running for 205km from Mons to Rocourt, it was notably shorter than in previous years and was won by Sylvain Grysolle, one of the first Classics specialists who after the War would go on to win the Ronde van Vlaanderen and the Omloop Het Volk.

Cyclists born on this day: Tara Whitten (Canada, 1980); Jack Bobridge (Australia, 1989); Dimitri de Fauw (Belgium, 1981, died 2009); Mirco Lorenzetto (Italy, 1981); Richard Groenendaal (Netherlands, 1971); Des Fretwell (Great Britain, 1955); Pascal Hervé (France, 1964); Benno Wiss (Switzerland, 1962); Michael Schiffner (East Germany, 1949); Vinko Polončič (Yugoslavia, 1957); Walter Tardáguila (Uruguay, 1943); Thomas Hochstrasser (Switzerland, 1976).

.jpg)