|

| Stage 9, 1922 |

|

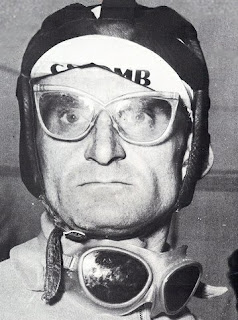

| Robert Jacquinot |

|

| Philippe Thys |

|

| Firmin Lambot |

Afterwards, many fans and the press said that he'd won through luck (or the bad luck of others) rather than through skill. He hotly contested this - he had been, he pointed out, just eight minutes behind when Heusghem was given his penalty, and he might very easily have made it up on the last 773km to Paris. Nevertheless, the French considered Alavoine (the only Frenchman in the top five, funnily enough) to be the moral winner and celebrated him as such.

1947 consisted of 21 stages covering 4,640km and was the first Tour since 1939, the Nazis having invaded France before the 1940 edition could take place. Just as before the War, the race was open to national teams rather than trade teams financed by commercial sponsors - Germany, however, was not invited; as much due to concerns that the safety of their riders could not be guaranteed should the French public decide to extract revenge down some lonely road as out of hatred for what had happened during the conflict. The Italians, meanwhile, were; but their team was composed of Italians resident in France as the peace treaty between the two countries had not yet been formalised and so, legally, they were still at war. There had been plans to invite a British-Dutch team too, but after the Dutch riders complained to the organisers that the British riders were no good it became a Dutch-French team instead.

|

| Jacques Goddet |

The race did not automatically cross the road with them, though: Sports and Miroir Sprint, two popular magazines, had joined forces and were bidding to take it over. Rather than giving it to whichever title could offer them the most money for the honour, like most governments would have done, the French government decided that a better way would be to let them both organise races on the same sort of scale as the Tour and then choose whichever one did the best job. L'Equipe enlisted the assistance of Le Parisien Libéré (owned by Émilion Amaury who, in 1962, would join Goddet as co-director of the Tour. Later, he would buy L'Equipe and began building the empire that became the Amaury Sport Organisation - which owns and runs the Tour to this day). L'Equipe's race, La Course du Tour de France, was judged most successful; the right to revive the Tour was theirs.

The 1947 Tour, Stage 2

Many races had carried on through the war, but they were one day events on the whole (the Nazis requested the Tour's organisers to continue, but were met with flat refusal), which combined with so many riders from before the War now being too old - and some, of course, no longer alive - meant that nobody really had any idea who might be in with a good chance. Ferdy Kübler (spelled that way, rather than "Ferdi" as is more common, because that's how Ferdy himself prefers it) won the first stage and was immediately earmarked for future success, but he wasn't yet the snorting, half-mad powerhouse that he became a few years later. Then René Vietto won Stage 2 and took the yellow jersey; since he'd come third in 1939 and was (undeservedly) beloved by the French public due to an artfully-cropped photograph taken at the 1934 Tour and had become symbolic for them of a generation of riders that had been robbed of their best years, he immediately became favourite despite being nearly 40.

|

| Jean Robic |

Another Franco-Italian, Fermo Camellini took Stage 8, then Vietto won Stage 9 and Camellini repeated his success by winning Stage 10 - these would be his only Tour stage wins. Édouard Fachleitner, Henri Massal, Lucien Teisseire and Albert Bourlon (who escaped right at the start and rode out on front for the full 235km, the longest breakaway of any post-war Tour) won the next four, but Vietto remained in yellow, It was on Stage 15 in the Pyrenees that little Robic really took flight and revealed that while he was built like a sparrow, he had the wings of an eagle; he simply rode away from the rest of the field and won the stage by 10'43". He was much more than a rider of considerable note now: he was a very real contender for the General Classification.

Still, Vietto wore yellow and he was expected to do well on Stage 19, at 139km the longest individual time trial in Tour history. In fact, he lost a significant amount of time - some people, presumably fans, said this was because he was mourning the death of a friend in a motorcycle accident; others swore that he had been seen swigging from a large bottle of cider as he tackled the parcours. Raymond Impanis won, Pierre Brambilla - who came fifth - earned enough time to come out with the race lead. Robic came second, and improved his overall time considerably; at the end of Stage 20 he was third overall with a disadvantage of 2'58" behind Brambilla.

|

| Pierre Brambilla |

Fachleitner knew that this was the case, and 100,000F was a very great deal more than he stood to win if he rode for himself; so he agreed. Schotte got to the finish line long before them but, once stage win time bonuses were awarded Fachleitner came second, 3'58" behind Robic - who had married a short time before the Tour and promised his wife the yellow jersey as a gift - whose overall time was148h11'25". According to legend Brambilla, who was third with +10'07, was so disgusted at what he saw as having been robbed of victory that he took his bike home to Annecy and buried it in the garden, fully intending to never ride again (he did, though, including four more Tours).

Fausto Coppi won the Tour in sensational style in 1949, the year he beat Gino Bartali, then stayed away in 1950 after breaking his pelvis at the Giro. In 1951, he was mourning the tragic death of his brother Serse. In 1952, therefore, he had a point to prove.

|

| Raphael Geminiani |

Rik van Steenbergen (whom, some estimates claim, won almost a thousand races during his 23 seasons as a professional - though other, probably more accurate, estimates put the figure far lower) won Stage 1 and took the yellow jersey for two days. André Rosseel won the second stage, then Nello Lauredi won the third and wore the maillot jaune for four days. Stage 4 brought the only Tour stage win of Pierre Molinéris' career and there was controversy after Géminiani and Robic escaped together in a break. Robic refused to do any of the work, drafting behind Géminiani all the way, then told journalists afterwards that he'd ridden intelligently because by saving energy in this way he had increased his chances of winning overall. That night, in the hotel, the hot-headed Géminiani (whose first Tour was in 1947, when Robic won) went after him and pushed his head into a sink full of water - which probably earned him a few new friends because Robic, for all he was a beautiful climber, was not a pleasant character at all.

Luxembourgian Bim Diederich won Stage 5 and briefly got the fans wondering if he might turn out to be a GC contender as he'd worn yellow for three days in 1951, but then Fiorenzo Magni got away on the next stage and won with a sufficient advantage to take the overall lead. He only had the maillot jaune for one day before losing it in the Stage 7 time trial, which Coppi won, and the jersey went back to Lauredi again. Stage 8 was the first in the Alps and Géminiani won - Magni and Lauredi remained together all the way to finish line, marking one another's every move; Magni was second over the line 5'19" later, but the 20" bonus he received earned him another day in the yellow jersey.

|

| Walter Diggelman |

Believing that team leader Coppi - of whom he was completely in awe, and to whom he had dedicated himself - would be furious, he burst into tears (some accounts say that Carrea was told he'd become race leader on the finish line and that he never went back to the hotel, nor were the police ever involved. Others say that he was told, then fled back to the hotel in panic. I like the version in which he didn't know until the police found him best, and since we'll never know for certain what happened - unless someone risks spoiling the story by delving too deeply into history, you can pick whichever version appeals most to you). On the podium, Carrea was distraught, eyes fixed firmly on the ground in shame except for frequent furtive glances about him for Coppi, whom he expected to appear at any moment to extract terrible revenge.

|

| "Chin up, mate!" Coppi attempts to reassure Carrea |

The following morning, Carrea made a point of being photographed by journalists as he polished his leader's shoes. He died on the 13th of January this year, and his passing was not nearly as widely reported as it should have been.

|

| Bartali knew his career was at an end. He handed over his rear wheel - and the future - to Coppi |

The following stages came and went; Robic won another and so did Géminiani, Magni and Rosseel. Géminiani's win was Stage 17 after he escaped the peloton in a desperate attempt to make up his 52' disadvantage, but Coppi didn't even bother to chase him. On Stage 18 in the Pyrenees, Coppi was the first rider to the summit of the last mountain. On the way down, he sat up, enjoyed the view, even stopped at a cafe for a sandwich and a cup of coffee and didn't look at all concerned when the main field caught up with him - then he won the final sprint to the finish line. After Stage 21, he led by 31' and so in the time trial the following day he rode around the parcours looking like a recreational cyclist on a Sunday jaunt, came fourteenth and yet still led by 28' overall. 150,000 spectators, a new record, turned out to see him start the final stage in Vichy, and when he finished he won the Tour by 28'17". Carrea was ninth, 50'20" down, by far the best result of his ten-year career.

In 1959 there were 22 stages, covering 4,391km in total. 120 riders started Stage 1 in Mulhouse, only 65 finished Stage 22 in Paris. In 1952, the race had been broadcast on television for the first time; this had been so successful (not only in France, but throughout Europe and beyond) that in 1959, for the first time, a helicopter was used to gather footage. The race also experienced one of its first doping scandals when official Tour doctor Pierre Dumas intercepted a parcel containing strychnine - which in the right doses acts as a stimulant - destined for one of the teams.

Just as had for the last three years, the Frenchman André Darrigade won Stage 1, then Vito Favero who had finished second overall the previous year won Stage 2. A large group escaped on Stage 3, but at such an early stage and long before the mountains nobody was particularly concerned, though the ten minute advantage they won was a little higher than the favourites had estimated they'd get and stage winner Robert Cazala would keep the yellow jersey until the end of Stage 8. On that stage, he was unable to respond to Belgian attacks. Louison Bobet, who was known to be Cazala's friend, could have stayed with him and in all likelihood kept him in the maillot jaune for another day; instead - concerned more with maintaining his own time so that he would still have a shot at victory later - he went after them. Desgrange, who always wanted his race to be a heroic battle in which every man rode only for himself, would have loved it had he have still been alive to see it; the fans were less impressed. So too was the Belgian Eddy Pauwels, who became new overall leader - after being awarded the jersey, he went straight to find Cazala's wife and gave her his winner's bouquet.

The French team, which consisted of Jacques Anquetil, Raphael Géminiani, Bobet and Roger Rivière, had started the race as favourite for the Teams classification and could have taken control by this point; but now it became evident that having so many potential winners was a problem - they all wanted to be team leader and refused point-blank to work together. Rivière won the Stage 6 time trial, but due to the rivalry in the team not one of them won a stage. Just how much of a problem this would be became apparent in Stage 15, a mountain time trial on the dormant volcano Puy-de-Dôme. The Spanish team manager's decision to install Federico Bahamontes as team leader had, initially, seemed rather odd - after all, a General Classification contender needs to be an excellent all-rounder and while Bahamontes was a superb climber (he'd won the King of the Mountains twice already) he didn't even try on the the other stages. The French saw this as a serious oversight. However, that day Bahamontes showed the world that he was not just a superb climber - he was phenomenal. Not even Charly Gaul - who had a Tour, three Giri d'Italia, four Grand Tour King of the Mountains and, for one glorious year in 1958 before the drugs and the madness began to take their toll (and the weather had suited him), had been the rider that many still insist was the greatest grimpeur to have ever lived - could get within 1'26" of him; though to be fair to Charly, who hated hot weather, the day was far too warm for him to be at his best. That was why Bahamontes was team leader - he was so good that he only needed the mountain stages, the rest didn't matter, and now the maillot jaune was his.

Louison Bobet, who had been the first rider to win three consecutive Tours with his victories in 1953, 1954 and 1955, ended his relationship with the great race during Stage 18. Since 1955, when he had undergone major surgery to remove decaying flesh caused by an infected saddle sort from his groin, Bobet had not been the rider he once was and many of his rivals were probably surprised he was still around - in 1958, going against advice from his doctor (a most unexpected act, for Bobet was obsessed with health and hygiene in a way that seemed utterly odd to most riders of the day), he had entered the Tour and suffered terribly, amazing everyone when he not only finished, but did so in seventh place.

What he had suffered up in the unearthly realm of the Casse Deserte that year, though, was nothing compared to the ordeal that came in 1959. He had been very visibly ill for much of the race, so much so over the course of the two days prior to Stage 18 that even those who hated him (and there were many of those) to worry about his well-being. His body was near to total breakdown, yet somehow he found the determination to the top of the 2,770m Col de l'Iseran, high enough that altitude sickness becomes a real concern. Then, just as the road began to drop and gravity would have afforded him an easier time, he brought his bike and his career as a Tour de France rider to an end.

Bobet was so ill by this point that, swaddled in the thick overcoat that someone had placed around him and propped upright on the back seat of one of the cars that had followed him up the mountain, some onlookers thought he had died. Then the car was driven away, Bobet's bike left by the road in the care of Gino Bartali who had ridden up the Iseran when it first featured in the Tour in 1938, and who had turned out to support the Frenchman in what they both knew was his final Tour. Later, when he had been nursed back to health, Bobet was asked why he'd pushed himself so far, risking his life. "I had never climbed the Iseran," he replied. "It's Europe's highest road, and I wanted to ride up there."

Brian Robinson took Stage 20 with a lead of 20'06", the second time a Tour stage had been won by a British rider - he had also been responsible for the first, one year earlier. Stage 21 posed one final challenge for Bahamontes as it was a time trial. As it happened, he wasn't a bad time trial rider, in fact he'd been National Champion in 1958; but he knew he was very much outclassed by several others, especially on the French team. In the end, he didn't even get into the top ten and the Frenchmen Rivière, Anquetil and Saint took the top three spots. However, none of them won back enough time to take away the overall lead and, with one flat stage left, he had won the Tour de France.

Gaul and Bahamontes are rightly regarded as the greatest climbers in the history of professional cycling, but in 1959 they faced competition from an entirely unexpected source - Victor Sutton, who was British; British riders being considered in those days to be among the lower ranks of cyclists, despite Brian Robinson's Stage 7 victory a year earlier, and certainly not great climbers (indeed, to this day Britain has produced only two world-class grimpeurs, the Scotsman Robert Millar and Emma Pooley from England). Sutton has been so entirely forgotten today that Cycling Archives doesn't list a palmares for him and he has no page on Wikipedia, but his natural talent in the mountains, where he could keep turning a low gear at high revolutions per minute just like Gaul did, enabled him to climb from 109th place at the end of the first week of the Tour to 37th by the finish; on the Puy de Dôme time trial he recorded a time that remained the fastest for an hour and might have finished in the top ten in Paris had he not have shared Bahamontes' terror of descending - once over the summit, he seized up and lost large chunks of the time he'd gained on the way up. He returned to the Tour in 1960, another year older and wiser and believed by some to now be in a position to beat the Eagle and the Angel, but his season up to the race had been too hard and he suffered a minor heart attack in Stage 18, the Tour's last day in the Alps.

Sutton died on the 29th of July in 1999; alongside Robinson, he was one of the first riders to show the world that British cyclists could compete at the highest level of the sport, and he should be far better known than he is today.

In 1961, there were 21 stages and they covered 4,397km. Many of the names from 1959 were riding again, though much had changed during the intervening two years - Gaul was already burning out, since no personality as intense as his can last long; André Darrigade, Eddy Pauwels, Robert Cazala and others had developed into strong riders. Two notable absences were Roger Rivière and Federico Bahamontes - Rivière's career had come to an end at the Tour one year before when he tried to follow Gastone Nencini down a mountain (something that other riders said only a man with "a death wish" would ever dare attempt), plunged over the side and broke his back, while Bahamontes had decided to stay away after abandoning in Stage 2 last year. He'd be back in 1963 and 1964, and Anquetil extracted terrible revenge for 1959. Anquetil had won the Tour in 1957, but since then been unable to repeat it. When he won the Giro in 1960, he confirmed himself as one of the best riders in the world rather than an also-ran who once got lucky; but as of yet nobody knew just how good he was going to be. He had also learned in 1959 that a superstong team made of General Classification contenders was more likely to dissolve into internal rivalry and bickering than guarantee success, so this year he made sure that the squad was made up of men who would accept his command then ride for him - any only him.

Darrigade won the first stage for the fifth time in his career and thus became the Tour's first holder of the yellow jersey after getting away in a small break. Crucially, Anquetil was also in the break; by the end of the stage Gaul and Anquetil's few rivals were already at a five-minute disadvantage. That afternoon the race moved into Stage 1a, an individual time trial; Anquetil was fully expected to win that, and he did - with an advantage of 2'32", sufficient to begin the next day in yellow. Stage 2 took in some of the harsh roads that some of the riders already knew from Paris-Roubaix and, as happens so often in that race, they laboured their way over the parcours in atrocious weather with seven men (none of the favourites) abandoning. Darrigade won that one, too, but Anquetil still had the maillot jaune. Nobody had taken it from him by Stage 6 when disaster struck the Dutch team: a German rider, Horst Oldenberg, crashed during a descent of the Col de la Schlucht in Alsace and collided with Ab Geldemans, the Dutch team leader who then had to be helicoptered to hospital. On the Ballon d'Alsace (which had been the very first mountain in the Tour back in 1905), Gaul had a little bit of fun - apparently without effort, he dropped Anquetil during the last 500m of the climb and rode to a 10" lead, then he sat up and allowed the Frenchman to catch him. The message was plain: "I'm just amusing myself, toying with you. Later, I'm going to kick you to death."

|

| Jacques Anquetil |

Anquetil won on the 16th of July. as he did so, a race he'd probably never heard of was ending 315km away at Laeken in Belgium. Among the riders from the Evere Kerkhoek Sportif club was a stocky sixteen-year-old, making his race debut. He didn't win but, had Anquetil have been there to see it, he might have felt a sense of dread about the future: the boy was destined to take away his greatest cyclist crown in less than a decade's time. His name was Edouard Louis Joseph Merckx

|

| The biggest threats to Hinault in 1981 - Joop Zoetemelk (centre left) and Phil Anderson (centre right) (far left: Adri van der Poel; far right: Jan Raas) |

Hinault had won the Tour on his first attempt in 1978, then won another in 1979. In 1980 he'd injured his knees and abandoned. This year he was World Champion and he'd started the season in spectacular style and won Paris–Roubaix, the Amstel Gold Race, the Critérium du Dauphiné and the Critérium International; then he showed up at the Tour in better form that ever before and won the prologue, which immediately made him the favourite. Freddy Maertens won Stage 1a, then Ti-Raleigh won the Stage 1b team time trial. Johan van de Velde won Stage 2, Maertens won Stage 3 and Ti-Raleigh won the second team time trial in Stage 4.

In Stage 5, the race made its only visit to the Pyrenees that year. Hinault, Phil Anderson and Lucien van Impe rode in a break out in front of the main field, but van Impe got ahead in the last few kilometres and won by 27". Hinault was just ahead of Anderson as they crossed the line, but Anderson's total lapsed time was smaller and so he became the first Australian - the first non-European, in fact - to have ever led the Tour de France. He wouldn't keep the maillot jaune for long: Hinault was a superb time trial rider and took it from him in Stage 6.

|

| Bernard Hinault |

In 1981, Hinault was enjoying his best years and was destined to win two more Tours, two more Giri d'Italia (for a total of three) and another Vuelta a Espana (his second); but already new stars were shining.

Other cyclists born on this day: Egor Silin (USSR, 1988); Danny Stam (Netherlands, 1972); Sébastien Joly (France, 1979); Karen Darke (UK, 1971); Martinus Vlietman (Netherlands, 1900, died 1970); Rory O'Reilly (USA, 1955); Ardito Bresciani (Italy, 1899, died 1948); Jimmy Swift (South Africa, 1931, died 2009); Guillermo Mendoza (Mexico, 1945); Oswaldo Frossasco (Argentina, 1952); Clemilda Silva (Brazil, 1979); Anriette Schoeman (South Africa, 1977); Thierry Marie (France, 1963); Antonio Giménez (Argentina, 1931).

No comments:

Post a Comment