|

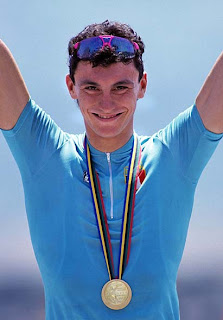

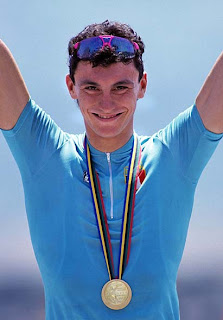

Fabio Casartelli

16.08.1970 - 18.07.1995 |

On this day in 1995, during Stage 15 of the Tour de France, 24-year-old Italian rider

Fabio Casartelli lost control of his bike whilst descending the Col du Portet d'Aspet at high speed. Several other riders were also involved in the crash but got away with injuries of varying severity; Casartelli's head struck the low wall running alongside the road. Doctors reached him within ten seconds, but although television cameras showed him lying on the tarmac in a pool of blood for only a second or two it was obvious to fans that he had suffered massive head injuries and was very badly hurt indeed. He died in the helicopter on the way to hospital.

The next day, his Motorola team crossed the finish line together with the other riders following slowly behind them. Prizes were handed out as normal, then all recipients pooled them and donated them to Casartelli's family. Lance Armstrong, also with Motorola, dedicated his Stage 18 to him and there is now a memorial at the spot where he fell. Since 1997, the Youth category at the Tour has been known officially as the Souvenir Fabio Casartelli.

|

Amy Gillett

09.01.1976 - 18.07.2005 |

Today is also the anniversary of the death of

Amy Gillett, who was born in Adelaide in 1976. Originally a world-class rower, Amy had been identified as a track and road cyclist with enormous potential and was predicted to win medals at the 2006 Commonwealth Games but was killed in Germany when a driver lost control of his car and ploughed into a group of cyclists with whom she was training in 2005. Five of her team mates were seriously injured, two sufficiently so that it was thought they also might die. Amy was 29 when she died and was studying for a PhD. She had been married for less than a year and a half.

The Amy Gillett Foundation was set up in her honour, an organisation that aims to cut cyclist fatalities on the road to zero by encouraging safer cycling and increasing awareness of cyclists among other road users as well as funding two scholarships per annum, one to a young female athlete and one to a researcher whose work will assist in reducing cyclist deaths on the roads.

You can learn more about their work here.

Gino Bartali

Often, we describe Tour de France winners as heroes - which to cycling fans they are, but to the rest of the world all they've done is won a bike race. Gino Bartali, however, truly

was a hero. Born in Pont a Ema on this day in 1914, he was the third child of a farmer and was raised in a poor household. His family were deeply religious, and his Catholic faith shaped his life every bit as much as his powerful physique and natural talent on a bike.

|

Gino Bartali, who was said to have "looked like a boxer but

climbed like an angel" |

At the age of 13 he began racing after being encouraged by colleagues in a local bike shop where he worked to support his family. Success as an amateur brought his first professional contract with Aquilano in 1931, but his career didn't really take off until he joined Frejus in 1935 - in his first year with them he won a number of one-day races, the Tour of the Basque Country, one stage and the overall King of the Mountains at the Giro d'Italia and the National Road Race Championship. At the Giro the following year he won three stages, the King of the Mountains and the General Classification but almost gave up cycling forever when his brother Giulio was killed in a crash while racing. However, he was convinced to continue, and in 1937 he won another National Championship and the Giro's King of the Mountains for the third time and General Classification for a second time.

Bartali entered the Tour de France for the first time in 1937 and won Stage 7, but on Stage 8 he was in a collision on a narrow wooden bridge and fell three metres into a river where he was very nearly swept away by the current - thankfully, Francesco Camusso was nearby and managed to grab hold of him and haul him out. He continued, but lost significant time in the next stages and abandoned in Stage 12. Having been brought up to be respectful, he went to Tour director Henri Desgrange before publicly announcing his decision to leave and Desgrange was touched that he did, because no other rider had ever thought to do so before: "You are a good man, Gino," he told the rider. "We'll see one another again next year, and you will win."

|

| Bartali in 1938 |

Desgrange was correct - in 1938, the Italian was able to defeat terrible weather and a very strong Belgian team, winning the toughest stage by a margin of 5'18" and finishing up with an advantage of 18'27". Georges Briquet, a radio commentator at the race, remembered: "These people had found a superman. Outside Bartali's hotel at Aix-les-Bains, an Italian general was shouting 'Don't touch him - he's a god.'"

Back in Italy a public subscription fund was started to reward him, the first man to donate money to it being Mussolini. Bartali's feelings about that haven't been recorded, but it's likely that it was a problem for him because, as he would later show, he was very much opposed to the Fascist leader's policies: it was known after the war that he had assisted in efforts to save the lives of Jewish Italians, but it's only comparatively recently that just how far he was willing to go to rescue a fellow human being from almost certain death has become known - not only did he courier information and fake documents around the Italian countryside, he personally transported Jewish refugees in a specially-designed trailer towed behind his bike across the Alps and into neutral Switzerland (if stopped by police, he explained that the trailer was deliberately constructed to be heavy and that towing it over the mountains was part of his training regime. If stopped, he'd almost certainly have been summarily executed or sent to a concentration camp). He was, therefore, a man whose courage went far beyond anything required in a bike race, as he proved when he was arrested and questioned by officers from the notorious SS secret service the

Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers-SS and would tell them nothing other than that he did what he felt was the right thing to do.

It's estimated that he was responsible for saving more than 800 people, yet Bartali never asked for reward nor even recognition, stating years later that "One does these things, and that's that" and insisting that the only medal he expected for what he had done was the one he wore upon his heart. In 2012, Israel's Yad Vashem announced that it was gathering further information in preparation for declaring him Righteous Among The Nations, an honour bestowed upon those who helped defend and save Europe's Jews from Fascist attempts to exterminate them.

.jpg)

When Bartali returned to the Tour in 1948, he found that the riders he'd known in the past had either been killed or injured in the war or were now too old to compete so he memorised the names of several other entrants in order to be able to talk to them during the race. Prior to traveling to France, the Italian team had argued before the race over whether Bartali or Fausto Coppi, who had already won two Giri d'Italia, should be team leader. The Tour organisers wanted both men in the race and even permitted a second Italian team so they could both lead, but eventually Coppi decided to sulk and refused to take part at all. Bartali was no longer a young man and whilst the war had taken its toll on everyone, he especially didn't look to be in good shape. He won the first stage, but then began to struggle and Louison Bobet had little trouble in gaining the overall lead and keeping it - though he collapsed after Stage 11, he recovered in time to win the next day.

After finishing Stage 12 with an overall disadavantage of 20', Bartali told his team mates that he was going to abandon; but they persuaded him to sleep on it and see how he felt the following day. He did so, but during the night was woken by a phonecall from Alcide De Gasperi - the prime minister of Italy. De Gasperi told him that Palmiro Togliatti, chairman of the Communist Party, had been assassinated. Could Bartali try his very best to win the next day, he asked, in the hope that such good news might prevent the populace rising up and thrusting the country into civil war?

|

| Bartali with Fausto Coppi |

Bartali assured him that not only would he win the stage, he would win the race - and he kept both promises. Stage 13 was won with a 6'13" lead after he took on and beat no less a rider than Briek Schotte, reducing the gap between himself and Bobet to 1'06". Then he won Stages 14 and 15 too, which gave him an overall lead of 1'47" - and, more importantly, united Italy in their support for him. He finished 32" behind stage winner Edward van Dijck in Stage 16, but because his rivals lost significant time his overall lead grew to 32'20" and from that point onwards. Ten years after his first Tour victory, he had won another - the longest period between two wins by any one individual in the history of the race. What he may have achieved had the War not interrupted his career and stolen his best years can only be guessed at.

Considering the eras in which he raced, it's remarkable that Bartali appears to have never resorted to doping. However, he was convinced that Coppi did (with good reason: Coppi later admitted it) and took a dim view of it, which led him to try to find evidence to support his suspicions. During the 1946 Giro he saw Coppi drink the contents of a small glass phial which he then threw into the undergrowth at the side of the road, so he stopped his bike and retrieved it. Later, he gave it to his doctor to investigate but it turned out to have contained a legal tonic. He then began closely monitoring his rival and, while he could never prove anything conclusively, became something of an expert in Coppi's habits and was able to predict how he would ride the following day:

"The first thing was to make sure I always stayed at the same hotel for a race, and to have the room next to his so I could mount a surveillance. I would watch him leave with his mates, then I would tiptoe into the room which ten seconds earlier had been his headquarters. I would rush to the waste bin and the bedside table, go through the bottles, flasks, phials, tubes, cartons, boxes, suppositories – I swept up everything. I had become so expert in interpreting all these pharmaceuticals that I could predict how Fausto would behave during the course of the stage. I would work out, according to the traces of the product I found, how and when he would attack me."

Bartali remained a competitive rider until he was 40, when a road accident ended his career. By that time he had given much of his money away to deserving causes and lost most of what remained in ill-advised investments. Fortunately, his fame was so great that he could earn a living from it, becoming the acerbic host of a popular television show and making a few cameo appearances in films. In old age he developed heart problems (not helped at all by an increasingly sedentary lifestyle - Miguel Indurain's manager once warned the five-time Tour winner to avoid being "like Gino Bartali" in his post-racing life) and underwent bypass surgery in 2000; but the operation was not successful. He was given the last rights and died ten days later, after which an official two-day period of mourning was declared throughout Italy. To this day, historians are still discovering the extents of his heroism - as recently as 2010 new evidence came to light proving that he had concealed a Jewish family in the cellar of his home, saving them from death at the hands of the Fascists he detested so much.

|

| Bartali wins the Tour, 1948 |

Russell Mockridge

Russell Mockridge was born in Melbourne on this day in 1928 and started his career with the Geelong Amateur CC, where he was nicknamed Little Lord Fauntleroy on account of his accent. Then he began winning races - a

lot of races - and people called him The Geelong Flyer instead.

Two years later he rode in the Olympics, but his race was ruined by two punctures; at the British Empire Games two years after that he won two gold medals and a silver. Mockridge was selected for the 1952 Olympic team but initially said he would turn down the invitation due to a requirement that athletes on the team remained amateur for two years - no less a figure than Hubert Opperman personally saw to it that the rule was reduced to one year, and Mockridge won another pair of gold medals. He did indeed turn professional a year later and in 1955 came 64th at the Tour de France - one of only 69 riders from 130 starters to finish the race.

Mockridge died on the 13th of September 1958 when he collided with a bus some 3.2km from the start of the Tour of Gippsland. He was only two months past his birthday and left behind his wife and three-year-old daughter.

On this day in 1947,

Federico Bahamontes entered his first race - and won it. On this day in 1959, he won the Tour de France.

Leandro Faggin, born in Padua in this day in 1933, won two Olympic gold medals and held three World Championship titles over the course of his career. He died at the age of 37 of cancer on the 6th of December 1970, and since 2000 is frequently included on lists of probable dopers.

Other cyclists born today: Rafał Furman (Poland, 1985); Martin Stenzel (West Germany, 1946); Sergey Kucherov (Russia, 1980); Joseph Racine (France, 1891, died 1914); Stephen Hodge (Australia, 1961); Michael Neel (USA, 1951); José Velásquez (Colombia, 1970).

.jpg)